Everyone knows that governments printed – but why? There are a lot of questions we believe are worth answering to have a deeper understanding of the current macro climate. In the third part of our macro series, we will dive into the immediate effects of COVID and the ongoing issues that are a direct result of the pandemic!

TLDR

- The practical halt in economic activity because of lockdowns had a huge negative effect on productivity and employment.

- To make up the difference, governments around the world borrowed (printed) huge quantities of money to bridge the gaps between lockdowns.

- Increased money supply led to widespread inflation.

- The Eurozone is facing a crisis on multiple fronts – energy prices and sovereign debt will play a huge role in policy-making within the EU.

- It is not clear to what extent the negative effects of quantitative tightening will be going forward.

Lockdowns

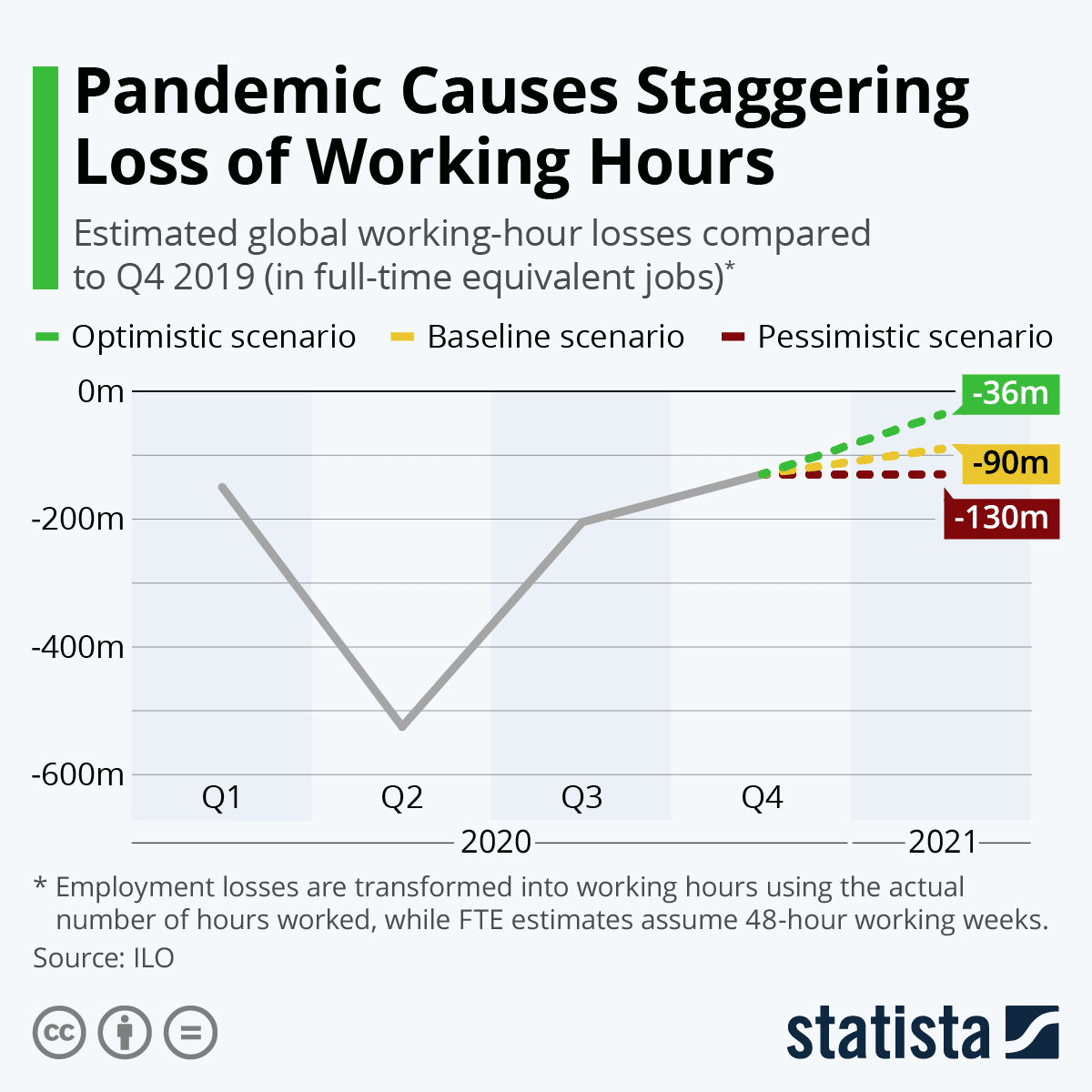

Arguably the biggest effect of COVID during the lockdown period was the loss of working hours, especially throughout 2020. In the early stages of the pandemic, governments were unsure of the severity of the virus, and so the decision was made to implement lockdowns to limit the spread. This created a huge loss in output, and for most countries around the world, the bill for wages was, for the most part, subsidised by governments.

The effect of all these hours lost was a loss of productivity equivalent to 255 million full-time (48-hour working week) jobs throughout 2020. Obviously, the uncertainty for those subjected to lockdowns was huge and governments stepped in to try and ensure that when lockdowns ended, there were jobs for these people to go back to. It goes without saying – the cost of this was massive.

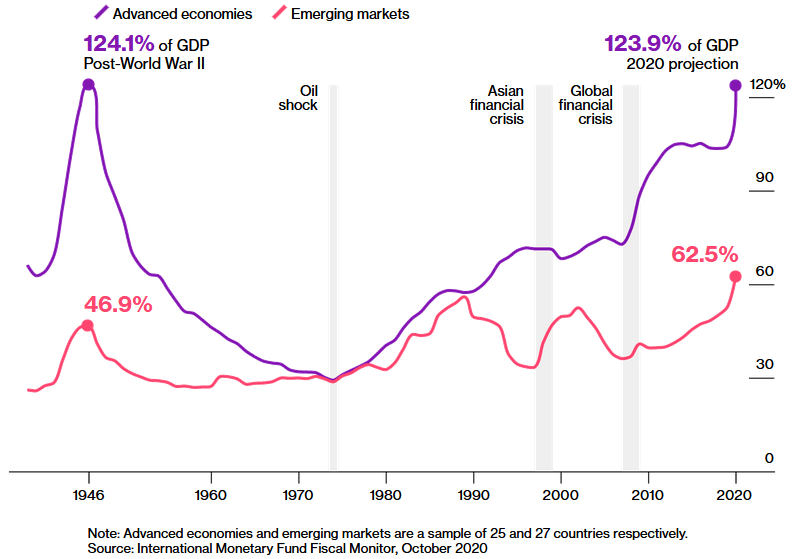

Debt was used to subsidise wages and businesses – global government debt increased by $19.5 trillion throughout 2020. Workers were unable to work, and many sectors were unable to generate revenue. This additional, unexpected, black swan event was a “once in a generation” economic crisis (the second in just over a decade), which came at a time when economies were still recovering from the “Great Recession” of 2008.

The money to pay for all of this was largely “printed” by central banks, which links back to our inflation article. Obviously, the contribution to the inflation situation the world is facing now is in large part attributable to this period of printing. The money did not come from productivity as the world was locked down. The simple law of inflation is that adding to the money supply (without comparable economic growth) makes existing money worth less when compared to the goods and services paid for.

Central bank rates were low, so this was largely affordable. However, with central banks now being forced to raise interest rates to combat inflation, the affordability of this debt is becoming a growing issue in some places.

Eurozone

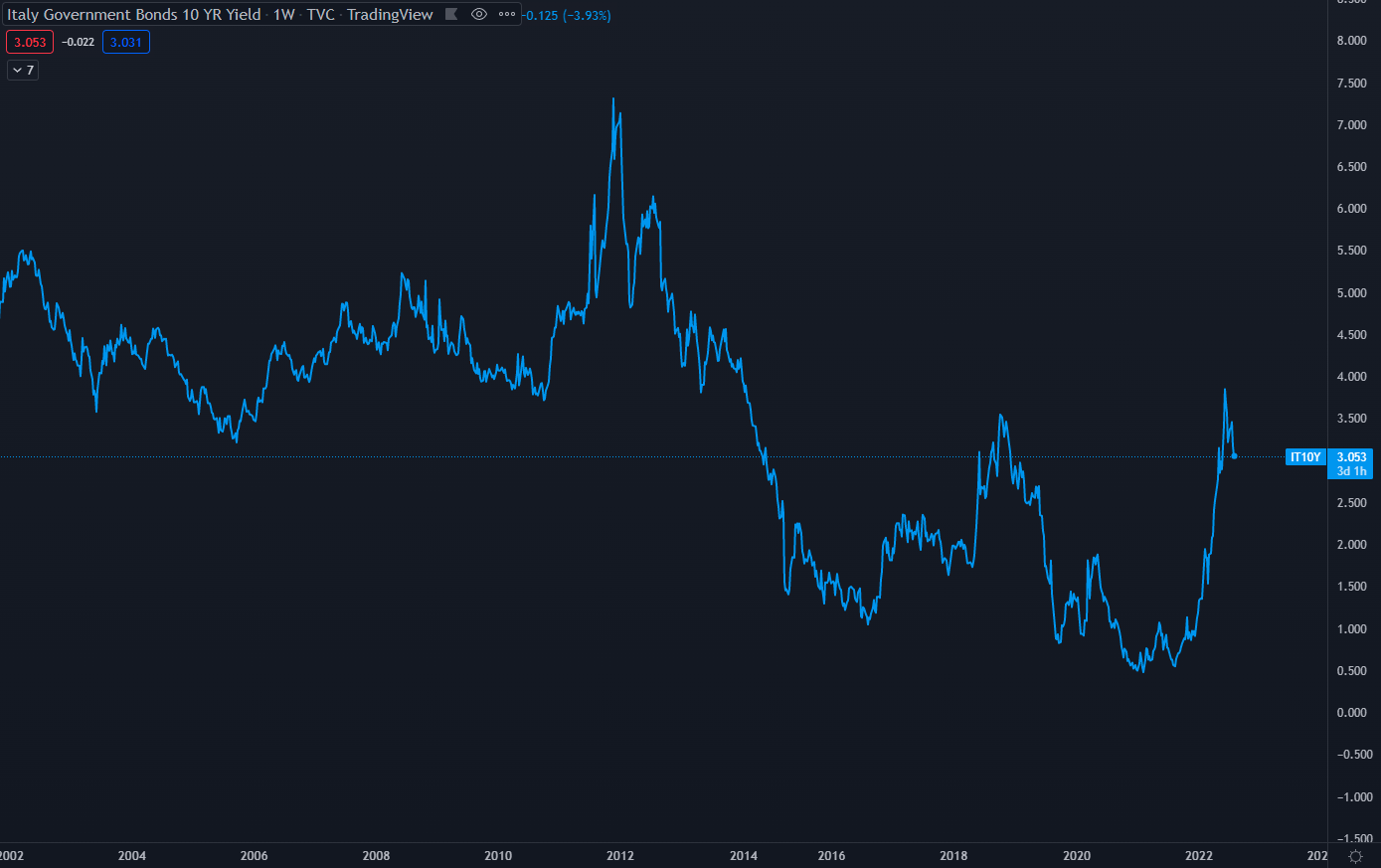

As stated in the previous article, Europe is currently facing an energy crisis as a result of the geopolitical situation in Eastern Europe. However, this is not the only source of problems for the Eurozone. There are fears that several EU countries are facing debt problems over and above external pressures. Italy is the largest such example – the chart below shows Italian 10-year government bond yield (the interest Italy pays on its debt):

As can be seen, the interest on Italian debt has grown significantly over the last year or so. The European Central Bank had been buying Italian bonds as part of the wider EU quantitative easing program. However, with the new restrictive policy in the Eurozone, there are fears that Italian borrowing rates will be far higher than that of other Euro countries like Germany – this is unacceptable in a single-currency system.

An Italian sovereign debt crisis would be a huge issue for markets since Italy is Europe’s third-largest economy and would batter an already weak Euro. The EU has set budgeting rules for Italy to receive continued support – Italy is what’s known as “too big to fail”. For perspective, the Greek Debt Crisis in the early 2010s rocked the Eurozone.

10-year bond yields reached almost 40% - a rate that was unsustainable, and default was on the cards. This threatened to spread to other indebted EU nations like Ireland, Portugal, and Spain. Such a small economy in Europe was able to have such an outsized effect because of its inclusion in the Eurozone. It was also due to the small size of the economy that effective measures could be put in place, and bailouts were viable. This is certainly not the case with Italy.

With the collapse of the Italian government earlier this year and elections due later, there were fears that the new regime would ignore EU rules and be cut off from this source of funding, causing interest rates to skyrocket further. The situation in Italy is something to be aware of and keep an eye on.

Conclusion

The era of quantitative easing is over – the main battle for central banks right now is combating inflation. It remains to be seen what impact restrictive policies will have on economies, and there are clear signs of the effects of these policies already. The slowdown in economic activity in the US and globally runs the risk of another widespread recession that could dwarf that of 2008.With debt levels already near all-time highs not seen since the 40s, the world is likely not able to implement the kind of quantitative easing a recession of that magnitude could require. Indicators we would be looking for would be a crisis in the Eurozone, continued pressure on energy prices in Europe, and the effect of European Central Bank quantitative tightening on highly indebted countries like Italy, as outlined above.